Exploring the NBA’s Three-Point Revolution: A Deep Dive into the Current State of Play

When the defending champion Boston Celtics launched a staggering 61 three-pointers on opening night against the New York Knicks, tying the second-most attempts in a regulation NBA game, it was more than just a nationally televised blowout. It ignited a season-long debate about the volume of three-point shots in the NBA. The Celtics’ performance was a catalyst, sparking discussions about whether there can be too many three-pointers in a game.

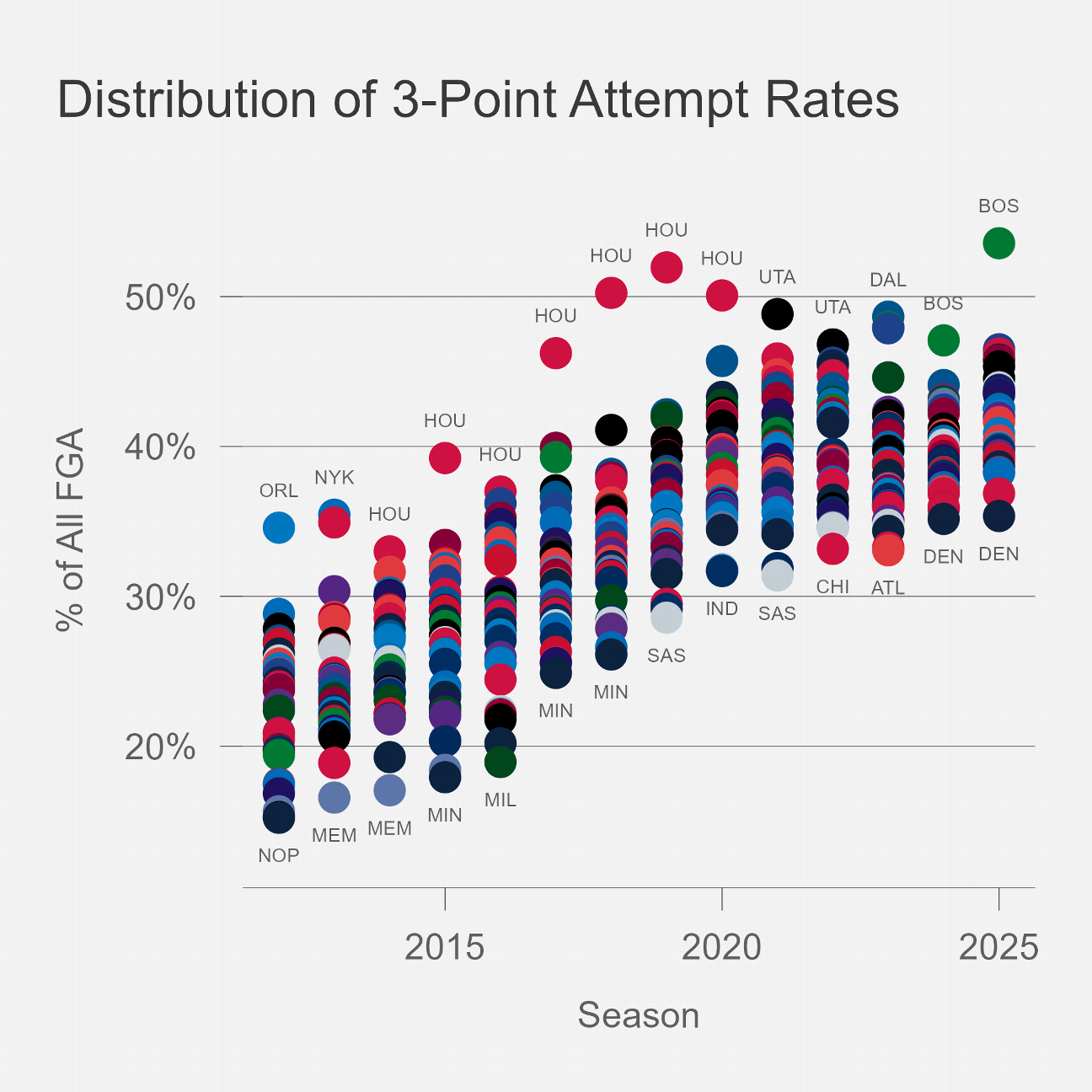

It’s not just the Celtics who are pushing the boundaries. After stabilizing around 35 three-point attempts per game over the past five years, which was already a 50% increase from a decade ago (22.4 per game), the rate has climbed to 37.5 so far in the 2024-25 season. This increase has coincided with declining national TV ratings early in the season, leading some to point fingers at the three-point revolution as a convenient scapegoat.

Despite the chatter, the league’s analysis indicates that fans are generally positive about the NBA’s style of play and the volume of three-pointers. As a result, no substantial changes are expected in the near future. However, that hasn’t stopped Daryl Morey, one of the pioneers of the three-point revolution and the president of basketball operations for the Philadelphia 76ers, from expressing concerns. At this month’s MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, Morey stated, “we have hit the point where [the three-pointer is] turning toward making the game worse.”

Celtics Pushing the Envelope — and Narrative

Just a year ago, it wasn’t clear that shooting more threes was the optimal strategy for NBA teams. The low-hanging fruit of converting catch-and-shoot two-pointers into more valuable three-point attempts had already been picked. During Morey’s tenure with the Houston Rockets, shooting more threes was essentially a hack. Between 2004-05 and 2018-19, the team that attempted the most threes in a game won 52% of the time, enough to put a team three games above .500 on its own. However, this trend reversed, and during the 2023-24 regular season, teams that shot more threes won just 48% of the time, marking the fourth time in five years they had been below .500.

But the trend flipped again in the 2024 playoffs. The team that took more threes went 51-28 (.646), and the top two teams in three-point attempt rate during the regular season met in the Finals, with Boston defeating the Dallas Mavericks. Starting with the Celtics’ opening night win, when they tied the NBA record by making 29 threes and spent the last five minutes attempting to break it, it became clear that three-pointers would be on the rise.

Evan Wasch, NBA executive vice president of strategy and analytics, told ESPN, “It is interesting to contemplate an alternate universe where that game didn’t happen the way it did to see whether one game could have driven such a significant narrative. But it certainly does seem that was a launching-off point for a lot of the discussion that then sustained itself through the coming months.”

The NBA’s national TV viewership was down during the first two months of the season, with three NBA double-headers competing against a highly rated World Series between the Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Yankees. This included games featuring the Knicks and Los Angeles Lakers on the same night as the thrilling Game 1.

Wasch explained that the lagging ratings “created a window for people to pick their favorite issue — which this season was the volume of three-pointers — and attribute the viewership drop to the three-point revolution or the three-point increase without any evidence that was the case.” This perception might have influenced how fans watched the games. Wasch’s team found evidence in the league’s survey tracker and social media sentiment analysis that increasing frustration with the number of threes and style of play began to emerge a month into the season.

“That was a signal to us that either there’s a bit of a lag in this data and how fans perceive the game or some of the perception is actually being shaped by the conversation that’s going on,” Wasch said. Nonetheless, it’s undeniable that more three-pointers are being shot in NBA games than ever before. After a brief period when it seemed we might have hit peak threes, they’re back on the rise. And Morey believes he knows why.

‘It Breaks the Game’: Time to Adjust the Three-Point Shot?

When Morey used the Sloan panel — provocatively titled “Have the nerds ruined basketball?” — to encourage the NBA to make changes and reduce the volume of threes, it was akin to Frankenstein asking the authorities to stop his monster. Outside of all-time leader Stephen Curry, no individual is more connected with the growth in three-point rate than Morey, who designed the Rockets to push for long-distance attempts to heights not reached again until this season’s Celtics.

Starting with its G League affiliate in Rio Grande Valley, which served as a lab of sorts for the NBA counterpart, Houston cut out nearly all two-point attempts outside the paint while playing at a fast pace. The Rockets became the first team in league history to attempt more threes than two-pointers en route to a franchise-record 65 wins in 2017-18. Morey was so associated with the Rockets’ style of play that it was nicknamed after a portmanteau of his name and the book that introduced baseball analytics to the general public: “Moreyball.”

To be clear, Morey didn’t exactly object to the current rate of threes. Instead, his issue was a matter of game design. When the three-point line was first introduced, Morey argued, the dramatic benefit was a necessary inducement to get players to shoot from longer range — or, perhaps more accurately, for their coaches to let them despite a relatively low completion rate.

It wasn’t until 1986-87, the eighth year of the three-pointer, that the NBA collectively shot better than 30% from beyond the arc. It took another six seasons, in 1992-93, for the league to shoot well enough for the average three to be worth more than a point.

By now, with players shooting 36% on threes, the typical attempt produces 1.07 points. To make a two-pointer equally valuable, players would have to shoot 53.5%. Hence Morey discouraging his team’s players from attempting twos outside the paint, which the league collectively hits at a 42% clip — just 17% better than the accuracy on threes, far less than the 50% difference in value.

“If the best players in the league taking wide-open 8-to-15 foot shots is worse than a heavily contested, off-the-dribble three, that is bad for the game,” Morey said, “and I think it’s the responsibility of the league office to take a look at this because teams are just going to optimize.”

For the most part, the volume of threes isn’t a major talking point among league executives. They’re more concerned with trying to put together the best team possible than producing the most compelling product on the floor.

“I don’t think it’s the fault of the teams or the analysts out there because their job is just to win,” Morey said, “but to me the bottom line is [the three] was added many years ago and it’s 50% more than other shots. That’s simply too much. It essentially breaks the game.”

Providing the NBA’s perspective on the Sloan panel, Wasch countered that game design matters only to the degree it produces an entertaining product for fans. And the NBA is still finding that fans are more positive than negative about long-range shooting.

Too Many Threes? No Issue for the NBA — For Now

When asked about the three-point topic, NBA commissioner Adam Silver has acknowledged the possibility of tweaks to change the style of play.

“Historically, at times, we’ve moved the three-point line,” Silver said at the NBA Cup final in Las Vegas last December. “I don’t think that’s a solution here because then, I think when we look at both the game and the data, I think that may not necessarily [create] more midrange jumpers, if that’s what people want, but more clogging under the basket.

He added: “I watch as many games as all of you do, and to the extent that it’s not so much a three-point issue. But that [to] some of the audience, some of the offenses start to look sort of cookie cutter and teams are copying each other. I think that’s something we should pay attention to.”

By the All-Star Game in February, Silver struck a somewhat more optimistic tone about how NBA basketball is played.

“We’re paying a lot of attention to it,” he said. “I’m never going to say there isn’t room for improvement. We’ll continue to look at it and study it, but I am happy with the state of the game right now.”

Overall, Wasch’s summation of what the NBA has learned from fan research was quite similar.

“Generally it’s quite positive,” he said in response to Morey’s assessment. “Fans have loved the three-point revolution. They love pace and space, they love the speed and physicality of the players, they love shots around the basket. There’s a lot of positive trends there.

“There’s an open question whether we’re now going too far and need to scale back a little bit to bring back some of the fans who may have been disillusioned by what they’re seeing, but I certainly don’t believe that there’s this fundamental problem with the game design because all that matters is what product we put out there for the fans.”

The league’s survey panel shows younger fans are more positive about the style of play and volume of threes than older ones, though Wasch said the difference was not statistically significant. However, the tone of the discussion doesn’t always match the statistical reality.

On stage at Sloan, Celtics vice president of basketball operations Mike Zarren expressed frustration with the notion that all teams play the same because they all make heavier use of three-pointers than their predecessors. (This season’s lowest team in three-point volume, the Denver Nuggets, would have led the NBA as recently as 2013-14.)

“The media narrative that all the teams are coming down and playing one style of play and jacking threes, I think, is not true,” Zarren said. “Most of the discussion is not [about] Daryl’s game design discussion … It’s, ‘Everybody has to play the same style where we just come down and jack,’ and that’s not what’s happening in the NBA.”

Could We See Even More Threes?

Wasch noted his group had studied the variation in play types from team to team and found no difference in terms of the diversity from past seasons in the sample. Along the same lines, the difference in three-point attempt rates between Boston and Denver this season is just as large as the average gap since 1996-97. It’s the average, not the distribution, that has shifted.

Quietly, the Celtics have been moving back toward the pack in terms of three-point tries. Over the season’s first 25 games, Boston averaged 51.3 three-point attempts, good for 56% of the team’s shots from the field. Since then, the Celtics are down to a mere 46.5 threes per game, or 52% of all shots.

Still, as with the Morey-era Rockets, the Celtics’ playoff results as the likely No. 2 seed in the Eastern Conference will serve as a referendum on how many threes are too many — even if they lose to the East-leading Cleveland Cavaliers, who rank fifth in three-point attempt rate.

Conversely, a long postseason run by the Nuggets, who rank third in offensive rating, might serve as a needed reminder that there’s more than one way to succeed offensively.

Either way, we’re likely to see more threes before we see fewer. Younger players have driven much of this season’s increase in long-distance attempts, particularly off the dribble. Witness Victor Wembanyama, who attempted nearly nine three-point attempts per game in his second NBA season — more than former all-time three-point leader Ray Allen averaged in any season during his Hall of Fame career.

At some point, the NBA will run out of long twos to push back behind the line. The notion that players are being encouraged to turn down layups and dunks in favor of threes is a pervasive misconception about the analytics-based rise in three-point rates. The share of shots in the paint is largely unchanged in the 12 seasons for which we have Second Spectrum analysis of camera-tracking data, with higher rates in the past three seasons.

Nonetheless, despite the popular notion that teams will eventually sell out so much defending the three-point line that midrange shots become relatively more valuable, the only way other leagues have found to decrease their three-point rates has been to move the line back.

As recently as 2018-19, NCAA Division I men’s basketball games featured more threes as a percentage of all shots than NBA games, but the following season the line was moved back to the FIBA distance (a maximum of 22 feet, 1.75 inches, as compared to the NBA’s 23-foot, 9-inch max). The NCAA saw threes drop from 39% of shots to 37.5%, and the men’s pro game now easily outpaces top college games in long-distance attempts.

There might be a time when three-attempts increase to where they become half the shots leaguewide. For now, the three-point rates don’t seem like a problem for the NBA.

“When the data is clear, we act,” Wasch said. “We’re not just here with our heads in the sand. On this issue, I think what we’re saying is there may be space for changes, but we’re not at the point where something drastic is needed, and we’re not at the point where there’s definitely a consensus from stakeholders that we need to do anything at all.”

Originally Written by: Kevin Pelton